Mutual mentoring for policymakers: lessons learned

“It widened my view, made me realise there is so much I could do, and that I can push myself out of my comfort zone.” Mentoring participant

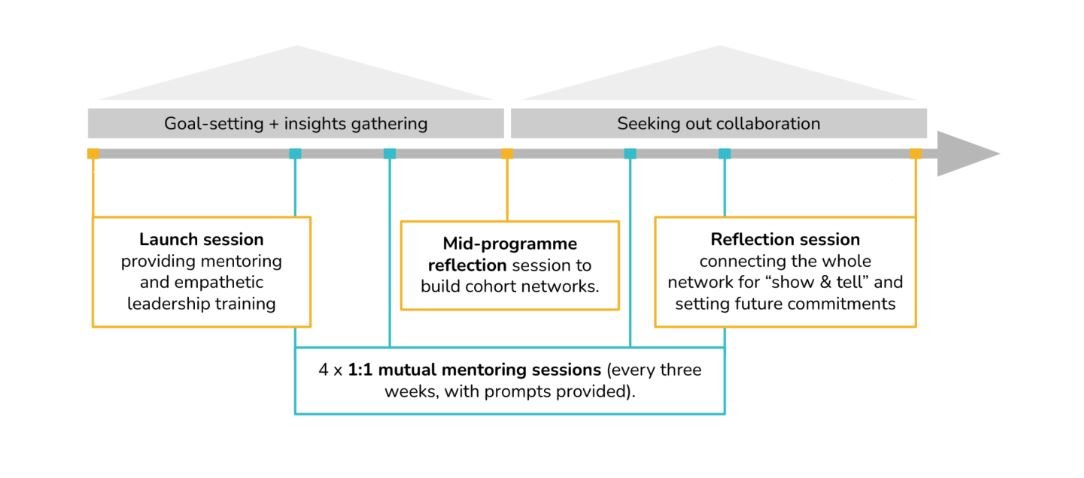

We recently delivered a seven-session mutual mentoring programme with Policy Profession, which was designed to support policy and service practitioners' professional development by using a mutual mentoring approach to co-create positive outcomes.

Policy Profession is the body that oversees all those making public policy in the civil service. When they asked us to design a mentoring programme that would connect policymakers with the Operational Delivery Profession, we jumped at the opportunity. The core purpose of Telescope is to bridge policy and practice, and we were delighted to see this idea being driven from within the civil service.

Through a combination of group sessions and individual pair work, we took our mentors on a journey to experience how strong and effective policy-frontline relationships can work, encouraging them to pioneer a new way of working. They practiced core skills in:

Active listening - to build human connection and discover each others’ shared values, and hold each other accountable on their personal and team goals;

Journey mapping - to share insights about the experience of a service user and challenges in frontline delivery;

Unpacking the black box of policymaking - to build a collective understanding about how public policy is made;

Prototyping solutions - to enable bold visions with respect to the shared challenges they face.

In the spirit of reflection, self development and sharing with an open mind, here are some of our key learnings from the programme - the good, bad and everything in between.

1. People want to work together

We were thrilled to receive over 50 responses to our request for expressions of interest from across 7 different departments within the civil service, reinforcing one of the core principles we build our work around: that there is an appetite on both sides (of policy and operational delivery) for better connection and collaboration. Exercises like our visualisation of the “black box” of policymaking were useful to dispel some of the myths around the policy process that existed among both groups. It helped our mentors understand how policy works, and talk about ways it could better integrate the experience of those on the ground.

2. Mutual mentoring works

We wanted to challenge the traditional top-down mentoring approach, which typically enables handing down experience from more senior roles. We also wanted to broaden the view of mentoring being only about personal goals to further your own career. Instead, our mutual mentoring journey was designed to be about supporting one another in a pair to learn more, better fulfilling both parties’ aims and mission in their roles, and improving society.

And we know it works. For those participants who completed the programme, we saw all our intended outcomes: people connected meaningfully with each other, learned from each other and shared insights about how things work on the ground, as well as how policies and decisions are made higher up. One mutual mentor commented that: “I didn’t realise how much more there was around the process, [my pair] helped me see that it’s much more complex.” Another reflected that they were “surprised to find out that the challenges faced by policy colleagues are very similar to mine when it comes to making it work.”

Our mentors also saw changes in their own career confidence, realising their strengths and looking for professional development opportunities beyond their current roles. “This programme has boosted my confidence hugely, I feel much more driven. It’s made me think about my career not from the perspective of “what gaps do I need to fill” but “what skills do I already have that I could be using better.”

It is notable that 8 out of the 10 mentors on this programme were women. We know there is confidence deficit among women in the workplace despite the great value that women can bring, so this kind of opportunity is even more important to foster. As an organisation of female founders, it is especially meaningful to us that we’re able to support women and other underrepresented groups to be confident, empathetic leaders and changemakers within their organisations.

3. Sustained engagement is hard

Unfortunately, several of the participants dropped out partway through the programme. Some degree of drop-off is always inevitable on programmes like this, but it becomes particularly difficult when the work depends on a two-way relationship between individuals. We identified this risk early during the design phase, and tried our best to mitigate it through careful selection of individuals who demonstrated the commitment and level of engagement needed. However, we also know that our public servants, whether in the policy or operational delivery profession, are very busy people, always pulled in different directions by the big challenges of the day. We also know that people often value things less when they are free, and the fact that this programme was paid from a central budget, rather than individual training budgets, may have reduced the incentives to stick with the programme for its duration.

4. And systems change is hard too

One defining feature of systems thinking is that systems like to perpetuate themselves, which makes shifting the status quo a very difficult task. We know from our previous programmes that public servants, and indeed anyone responsible for delivering services to the public, can find it especially hard to adopt the ‘fail fast’ approach of prototyping that we believe is needed to trial new solutions. There are many blockers to change, but senior buy-in is always an invaluable part of the process - and it’s one we can’t always secure over the timeframe of our programmes. It takes a lot of trust to ask a senior manager to let you try something new within a service, especially when the wellbeing of the public might depend on it.

For Telescope, it has made us reflect again on where the focus of our activities should be. We have always been proud that our work not only supports people to build relationships and other so-called ‘soft skills’ (which we don’t really see as “soft” at all), but also empowers them to be changemakers by testing and implementing solutions to systems challenges. But trying to straddle these different outcomes has always been difficult, and we often have to question whether we are trying to do too much. The connection between policy and frontline in itself is already so valuable, and we believe this change in working practice, moving towards a more collaborative approach, can have a profound impact on how policy is made. This is also where Telescope really offers unique value, so maybe it is time to focus our efforts. It’s not about lowering our ambitions, but tightening them.

We will be reflecting more over coming months, and look forward to trying out some of our ideas in future programmes. What is your experience of mentoring, and what do you think about the concept of ‘mutual mentoring’? We would love to hear your thoughts so please get in touch!